Udacity A/B testing notebook

notability notes: https://notability.com/n/in~CqsQl1aNsvE8mXX3Mn

Yancy

Overview

When A/B Testing is useful?

Useful: help you climb to the peak of your current mountain: the ranking changes (LinkedIn), the UI, response latency (Amazon, Google)…

Not Useful:

- test new experiences; old users may resist the new version (change aversion), or old users may all go for the new experience, then the test set has everything (novelty effect). Two issues to consider when it comes to a new experience: (1) what is your baseline of comparison? (2) how much time do you need for your users to adapt to the new experience so that you can say what is the plateaued experience and make a robust decision?

- the long-term effect is hard to test too, such as a website that recommends apartment rentals; note updating the brand or logo can’t use a/b testing, it’s surprisingly emotional and users need some time to get used to the new logo

- can’t tell you if you’re missing something

Hypothesis Testing and A/B Testing

Clinical trial: have a better quality of data and know more about each person

online A/B testing: more data, but lower resolution

Business example

-

Goal – if change the start button’s colour

-

Choose the metric:

CTR: click-through-rate: number of clicks/number of page views

Click-through-probability: unique visitors who click/unique visitors to the page

use rate to measure usability, use probability to measure the impact

-

Distribution – Binomial (2 types of outcomes, independent events, identical distribution)

-

Hypothesis testing – $H_0: P_{con} = P_{exp}$ , cut-off=0.05

the calculation of the confidential interval and hypothesis testing is on the note.

substantive (statistician) and statistical significance (engineer) are the same, it is about repeatability. And a 2% CTP change is practically significant.

H0 is true H0 is false accept H0 $1-\alpha$ $\beta$, Type II error reject H0 $\alpha$, Type I error, <5% $1-\beta$, power, >80% α is the probability of Type I error in any hypothesis test–incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis.

β is the probability of Type II error in any hypothesis test–incorrectly failing to reject the null hypothesis.

α风险代表生产者的风险,β风险代表使用者的风险。在产品出厂时通常要做终检,α风险的含义就是将合格的产品检验为不合格的产品,要么返修、要么报废,总之生产者要承担损失;β风险是把不合格的产品当成合格的产品流到使用者手上,给使用者带来损失。

P-value is the probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as a result actually observed, under the assumption that the null hypothesis is correct.

Sample Size

If the sample size doesn’t change,α larger, β smaller; so if α and β smaller, increase the size

Use the online calculator https://www.evanmiller.org/ab-testing/sample-size.html to calculate the sample size.

Baseline conversion rate: estimate CTP before making change. Higher CTP in control (but still less than 0.5), $SE=\sqrt{p(1-p)/N}$, larger variance, increase the size.

dmin: minimum detectable effect. Increased practical significance level, decrease the size

increase confidence level: 1-α, increase the size

higher sensitivity: 1-β, increase the size

the decision of launching the new version is on the note

Four Principles of AB Test

- Risk: Minimal risk is defined as the probability and magnitude of harm that a participant would encounter in normal daily life.

- Benefits: the benefits are around improving the product.

- Alternatives: the fewer alternatives that participants have, the more issue that there is around coercion and whether participants really have a choice in whether to participate or not, and how that balances against the risks and benefits.

- Data Sensitivity: can re-identify the person from the data

there should be internal reviews of all proposed studies by experts regarding the questions:

- Are participants facing more than minimal risk?

- Do participants understand what data is being gathered?

- Is that data identifiable?

- How is the data handled?

Choosing and Characterizing Metrics

What to use metrics for:

1) Sanity Checking / Invariant Checking: to make sure the experiment is run properly. These metrics should remain unchanged between the control and experiment groups. 2) Evaluation: High-level business metrics, more detailed metrics that reflect the user’s experience with the product

Example: Choosing metrics

- CTR on the “start now” button

- CTP on the “start now” button

- Probability of progressing from a course list to a course page

- Probability of progressing from a course page to enrolling

- Probability of enrolled student paying for coaching

Update a description on the course list page—3

Increase the size of the “ start now” button—1

Explain the benefits of paid service—5

Difficult Metrics

- don’t have access to data

- takes too long

Example: Which metrics are hard to measure?

rate of returning for 2nd course—yes, has data but too long

average happiness of shoppers—yes, doesn’t have data

probability of finding information via search—yes, doesn’t have data

Other Metrics Techniques:

- Brainstorming to generate new ideas

- Validate possible metrics

- Develop validation techniques based on how the external vendors analyze the data

Gathering Additional Data

User Experience Research(UER)

Often only a few users but can go very deep

- good for brainstorming

- can use special equipment

- want to validate the results: with a retrospective analysis

Focus Groups

More users, but less deep

- get feedback on hypotheticals

- run the risk of groupthink

Surveys

- useful for metrics you can not directly measure

- can’t directly compare to other results

Example: Applying other techniques to difficult metrics:

Rate of returning to 2nd course: Survey to find out the reason to return to 2nd course. If something measurable predicts the return, can use it as a proxy.

Average happiness of shoppers: Find things correlated – survey at the end of the purchase, or a UER.

Searchers find the information they were looking for: External data about information-finding research; a UER; Human Evaluation = pay human rator to evaluate your site

Possible proxies: Length of time spent; clicks on the results; follow-up queries

Example: Measure student engagement in class:

- External data

- UER: observe how students interact with the course

- Focus Group

- Survey

- Retrospective analysis: the behaviours correlated with students’ engagement in history

- Experiments

Mesure user engagement—4,2,5

Decide whether to extend inventory—3,1

Which ads get more views—1,2,5

Metric definitions

High-level Metric: CTP=#users who click/#users who visit

Def 1 (Cookie probability): For each time interval, #cookies that click/ # cookies

Def 2 (Pageview probability): #pageviews with a click within a time interval/ #pageviews

Def 3 (Rate): #clicks/# pageviews

Consider some more detailed information: e.g. a cookie and no click – after a day, the same cookie comes back, and 15 mins wait and then click – do you consider them to be the same record? Or page load and click are around midnight and fall under two days, do you consider them as same-day events or separately e.g. different browsers or platforms – might be different click-through rates, as the technology to collect the clicks are different

Example: a website visit record

o<—–5min—–>o<–30s–>o<——————–12h—————————>o

click no click no

def1: per min:2/3; per hour: 1/2; per day: 1; def3: 2/4

Filtering and Segmenting

External factors to consider: abuse on your site such as spam, fraud

Internal factors to consider: Some changes only impact a subset of your traffic (only English Traffic), or only impact some platforms.

Example: suspect click tracking issue: clicks counted twice on mobile, which graph would confirm the problem?

CTR over time—No; CTP over time—No; Both rate and probability on the same graph—No

CTR by platform—No; CTP by platform—No; Both rate and probability by platform—Yes

Summary Metrics

(1) Sums and Counts – e.g. number of users visiting the website

(2) Distributional metrics - e.g. means, median, percentiles.

(3) Rates or probabilities

(4) Ratio – range of different business models, but it is very hard to categorize

Sensitivity & Robustness

The mean is sensitive to outliers and heavily influenced by these observations; the median is less sensitive and more robust. This can be measured using prior experiments and A/A tests to see if the metric picks up any spurious differences.

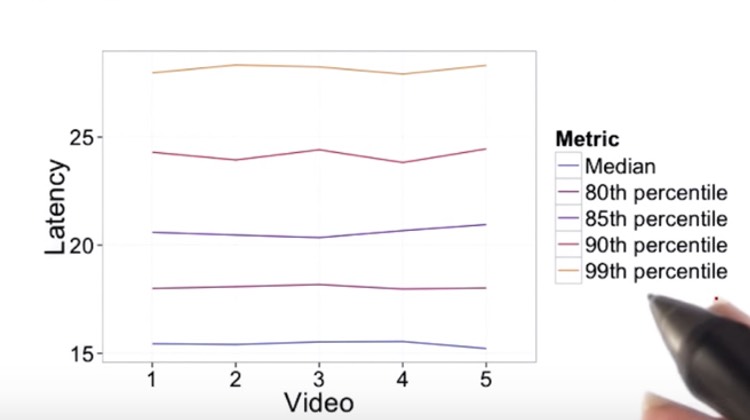

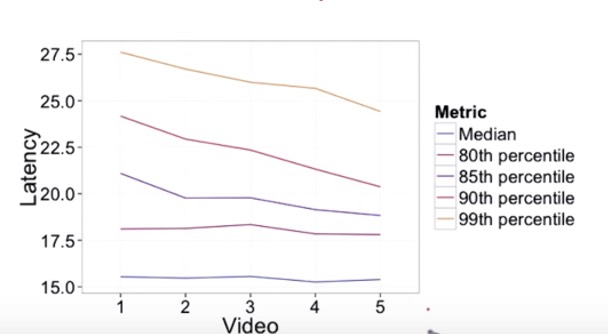

Example: Choose the summary latency for a video

Assume the videos are comparable. pic 1: distribution of similar videos Videos from 1 to 5 with decreased resolution. pic 2: distribution of experimental videos From pic1, 90 and 99 are not robust enough; from pic2, median and 80 are not sensible enough.

So 85th percentile is a good choice

Absolute or Relative Difference

- Absolute difference: just get started with the experiment and want to understand the possible metrics

- % change advantage: only need to pick one practical significance boundary to get stability over time

| Type of metric | Distribution | Estimated Variance |

|---|---|---|

| probability | binomial (normal) | $\frac{p(1-p)}{N}$ |

| mean | normal | $\frac{\sigma^2}{N}$ |

| median/percentile | depends | depends |

| count/difference | normal (maybe) | $Var(X)+Var(Y)$ |

| rates | Poisson | $\overline{X}$ |

| ratio | depends | depends |

Non-parametric methods

Analyze the data without making assumptions about what the distribution is.

Empirical Variances: estimate the variance empirically than analytically (make assumptions for the underlying data distribution—not true for complicated metrics; even for simple metrics, the variances could be under-estimated by using the analytical method)

Use A/A test to estimate the empirical variance of the metrics. AA实验就是实验组和对照组的实验配置完全一样,主要为了测试本次实验效果的波动性。理论上AA实验效果之间的差异应该是很小的,但如果实验效果差异很大,说明本次实验变量本身的效果波动就较大,原先AB 实验的效果也不够置信。

With A/A tests, we can

- Compare the result to what you expect (sanity check)

- Estimate variance empirically, use the assumption about the distribution to calculate the confidence

- Directly estimate confidence interval without making any assumption about the data

(1) Example 1: Sanity Checking

(2) Example 2: Calculate empirical variability link

(3) Example 3: Directly estimate the confidence interval link

**Bootstrapping: **If you run one A/A test, take a random sample of data points from each side of the experiment, and calculate the click-through probability based on that random sample as if it was a full experimental group.

Designing an Experiment

Choose the control and experiment group

Unit of diversion

user id: stable, unchanging; personally identifiable

anonymous id (cookie): changes when you switch browser or device; users can clear cookies

event: no consistent experience; use only for non-user-visible changers

device id: only available for mobile; tied to specific devices; unchanged by user; personally identifiable

IP address: changes when location changes

Example: a user first visits a website on a desktop and then changes to the mobile to continue the video. Is the group he was assigned changed?

desktop mobile homepage sign in visit a class watch video auto sign in watch video user id ☑️ cookie ☑️ ❓(may clear the cookie) ❓ ❓ ☑️ ❓ event id ☑️ ☑️ ☑️ ☑️ ☑️ ☑️ device id ☑️ IP address ☑️ ❓ ❓ ❓ ❓ ❓

Consistency of Diversion

Example: Which unit of diversion will give enough consistency?

| Experiment | Event | Cookie | User-id |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change reducing video load time | ☑️ | ||

| Change button colour and size | ☑️ | ||

| Change the order of search results | ☑️ | ||

| Add instructor’s notes before quizzes | ☑️ |

Ethical Considerations

Example: Which experiments might require additional ethical review?

Newsletter prompt after starting a course, user id diversion –no new information being collected

Newsletter prompt after starting a course, cookie diversion –yes, email address stored by the cookie

Changes course overview page, cookie diversion – already being done

Variability Considerations

Empirical variability may be much higher than analytical variability. The unit of diversion should be at least as big as the unit of analysis; otherwise, the same event might correspond to different groups, and the metric is not well defined.

Example: unit of analysis and unit of division–When would you expect the analytic variance to match the empirical variance?

Metric: CTR=#clicks/#pageviews; unit of diversion: cookie —no,unit of analysis: pageview

Metric: #cookies that view the homepage; unit of division: pageview — no, unit of analysis: cookie

Metric: #users who sign up for cooking/#users enrolled in any course; unit of division: user id —yes

Target Population

Need to decide who you are targeting in your users.

- Restrict the number before the official launch to avoid press coverage.

- check if the language is correct.

- If it works on older browsers

- Avoid overlapping between various experiments

- Only run your experiment on the affected traffic. The global data might dilute the changes.

The example is on the notebook

Inter- vs. Intra-User Experiments

Intra-user Experiment: you expose the same user to this feature being on and off over time. Interleaved experiment: expose the same user to the A and the B side at the same time. Typically, this only works in cases where you’re looking at reordering a list. Inter-user experiment: you’ve got different people on the A and B sides.

Population vs. Cohort

Cohort: define an entering class and only look at users who entered the experiment on both sides around the same time. Use cohort instead of the population when:

- looking for learning effects

- examining user retention,

- want to increase user activity

- anything requiring the user to be established

Example: have existing lessons and change the structure of lessons

unit of division: user id, but can’t run on all the users in courses— some have finished the course

so use the cohorts: limit the experiment to a subset of the population, and split them between control and experiment groups

Size of the experiment

Choice of the metric, unit of diversion, and choice of the population – these may affect the variability of the metric. Take these into account and determine the size.

Example: metric: CTR= #clicks/#pageviews, the unit of diversion: pageview or cookie

Analytic variability won’t change, but probably underestimate for cookie diversion;低估差异

Empirical estimate with 5000 pageviews, by pageview SE=0.00515, by cookie SE=0.0119

The size: assume $SE\sim \frac{1}{\sqrt{N}}$, dmin=0.02, diverting by pageview: 2600; by cookie: 13900

How to reduce the size of an experiment to get it done faster?

- Increase dmin, significance level alpha, or reduce power (1-beta) which means increasing beta

- Change the unit of diversion if originally it is not the same as the unit of analysis. 和指标中分母一样, reduce the variability, but new question: less consistent user experience

- Target the experiment to specific traffic. Unrelated traffic will dilute the result and impact the choice of practical significance boundary.

- Change metric to cookie-based CTP: may not help, especially using a short window for the probability

Duration and Exposure

We couldn’t run on all of the traffic to get results quicker for several reasons:

- safety to make sure the function works well;

- press, we don’t want a lot of people to know it before it works;

- other things impact the variability, such as holiday

Example: when to limit the number of users exposed?

change database — Yes, the effect could be huge

change the colour of the “start” button — No

allows Facebook login — Yes

changes the order of courses on the course list —No, low-risk change

Learning effect

When there’s a new change, in the beginning, users may be against the change (change version) or use the change a lot (novelty effect). But over time, user behaviour becomes stable, which is called the plateau stage.

Suggestion: Run on a smaller group of users, for a longer period of time.

Notice:

- choosing the unit of diversion correctly;

- the leaning effect is connected to the dosage: how often we see the change, then you probably want to be using cohort as opposed to just a population;

- risk and duration

Pre-periods and post-periods: A/A test before and after the experiment. Differences observed in post-period can attribute to the learning effect.

Analyzing Results

Sanity checks

Use invariants to do the sanity check – two types:

(1) population sizing metrics based on the unit of diversion

The experiment population and control population should be comparable.

(2) other invariants – the metrics that shouldn’t change in your experiment

Example: how to choose invariant metrics?

# signed-in users #cookies #events CTR on “start” Time to complete changes the order of courses in the course list; unit of diversion: user id ☑️ ☑️ ☑️ ☑️ changes infrastructure to reduce load time; unit of diversion: event ☑️ ☑️ ☑️ ☑️

Example: change the location of the sign-in button to appear on every page, unit of diversion: cookie, which metrics would make good invariants?

#events: yes, #cookies, #users all good

CTR on “start”, probability of enrolling, sign-in rate: no

video load time: yes, no backend changes

The data are randomly assigned to the control and experiment groups within the probability of 0.5. 检查实验组和对照组分配是否合理 checking procedure example is in the note

What to do if you find issues during the sanity check?

- Issues to check with the engineering team: Experiment infrastructure or Unit of diversion

- Retrospective Analysis: Recreate the experiment diversion from the data capture to understand if there is something endemic to what you are trying to do that might cause the situation.

- Pre and Post-period: If observe changes for invariant metrics in the post-period, check if similar changes exist in the pre-period. If so, there could be problems with the experiment infrastructure, setup, etc. If the changes are only observed in the post-period, it means the issue is associated with the experiment itself such as data capture.

The most possible reason:

- Data capture

- Experiment setup – didn’t set up filter correctly between control and experiment.

- System issues such as cookie reset (need to dig deeper and find out with the engineering team)

- The learning effect may take time. If the issues are observed at the beginning of the experiment, might not be a learning effect.

Analyze the results

Single metric

An example of single metric analysis is in the note

Hypothesis test and sign test conclusions do not agree: Need to take a look at the feature functions to see if it really functions differently for different sub-groups (e.g. platform).

pay attention to Simpson’s paradox!

| N con | X con | Nexp | Xexp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New users | 150,000 | 30,000(0.2) | 75,000 | 18,750(0.25) |

| Experienced users | 100,000 | 1,000(0.01) | 175,000 | 3,500(0.02) |

| Total | 250,000 | 31,000(0.124) | 250,000 | 22,250(0.089) |

Indicating that in addition to the control/experiment group, there is another dimension that would affect the metric.

Although for each subgroup it seems that CTR has improved, the overall CTR was not improved and cannot say the experiment is successful. Need to dig deeper to understand what caused the difference between new users and experienced users.

Multiple Metrics

As you test more metrics, it becomes more likely that one of them will show a statistically significant result by chance.

Example: For 3 metrics confidence level of 95%, what’s the chance of at least 1 false positive?

P(FP=0)=0.95^3=0.857 —Assuming independence P(FP>=1)=1-0.857=0.143

what if for 10 metrics: 95% confidence: 0.401; 99% confidence: 0.096

But a problem: the probability of any false positive increases as you increase the number of metrics Solution: Use a higher confidence level for each metric

-

Method 1: Assume independence: α_overall = 1-(1- α _individual)^n

-

Method 2: Bonferroni Correction, no assumption

but conservative: guaranteed to give α_overall at least as small as specified

α _individual= α _overall /n

-

Other methods:

FWER(familywise error rate): control probability that any metric shows a False Positive

FDR (false discovery rate): across a large number of metrics. FDR = E[false positives/rejections]

Drawing conclusions

Whether to launch an experiment or not??

-

Statistically and practically significant to justify the change?

-

Do you understand what the change can do to user experience?

-

Is it worth the investment?

Gotchas: changes over time

When you are ramping up the change, you may see the effect flatten out. Thus making the tested effect not repeatable. There are many reasons for this phenomenon.

-

Seasonality effect, event-driven impact;

Solution: use the hold-back method, launch the change to everyone except for one small hold-back group of users, and continue comparing their behaviour to the control group.

-

Novelty effect or change aversion: cohort analysis may be helpful.

Lessons learned

- Double-check, triple-check that your experiment is set up properly.

- Not only think about statistically significant but also business impact. Think about the engineering cost, customer support or sales issue, what’s opportunity cost, etc.

- If you are running your first experiment that has a big impact, you might want to run a couple of experiments and check the results to see if you are comfortable launching it.

- It is actually a business decision rather than a problem set of statistics.